A little bit of history was made last month. So far as I can tell it didn't make the news but I feel it should be recorded as it marks the culmination of an amazing 300-year story. This is long news.

'Decoding Harrison' was a one-day conference held at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich – one event in a year of celebrations marking the 300th anniversary of the Longitude Prize. If you've not encountered the story, this was a challenge set by the British Government in 1714 to devise a reliable mechanism for finding longitude at sea. This was an important problem for the British Navy and up to £20,000 was offered to anyone who could provide a practical solution.

The prize was eventually awarded to Yorkshire clockmaker John Harrison for his groundbreaking pocket chronometer H4. The clock, looking much like an over-sized pocket watch, was able to keep very accurate time even aboard ship. It allowed the ship's navigator to compute his own longitude from knowledge of the time in Greenwich and a local observation of mean solar time.

It was fitting then that Dava Sobel, the writer who brought Harrison's story to the world's attention, should chair the day. The conference room was full, around a hundred or so attendees including some important figures in British horology.

The first speaker of the day was the museum’s curator of Horology, Rory McEvoy, who outlined the problem Harrison faced. He explained the physics of pendulums and how pendulum clocks operate. These were the most accurate timekeepers of their day, but their operation is very sensitive to motion. A seagoing pendulum clock was never going to work.

Although Harrison is famous for his clocks his family trade was carpentry. Andrew King spoke of the horological ideas in his early wooden clocks. Harrison was able to reduce ware in key parts by using lignum vitae, a naturally oily wood, to self-lubricate the mechanism. Through his innovations, his clocks were achieving an accuracy of one second in thirty days. In his later years he published a pamphlet that made claims to one second in one hundred days. The validity (or otherwise) of this statement was to form the backbone of the day.

Our story jumps forward 250 years or so to the 1960's whereupon we meet another Yorkshire clockmaker, Martin Burgess. A lifelong admirer of Harrison, Burgess began construction of two clocks using modern materials but incorporating Harrison's ideas. Both clocks are beautiful. The Gurney Clock (Clock A) has been in Norwich since the early 80's and Clock B was until 2009, lying unfinished in Burgess' workshop.

The next speaker was the new owner and patron of Clock B, Don Saff. He told how he had purchased one of Burgess’ timepieces in New York and had subsequently sought him out in England. During his visit he discovered Clock B and set out to rescue and finish it.

Clock B was taken to the workshops of Charles Frodsham and Co to be completed. Philip Whyte, Roger Stevenson and Martin Dorsch, all from Fordshams, spoke in detail about the restoration process. Harrison had advocated a long pendulum with a relatively light bob. This goes against traditional horological wisdom but is one of several key features found in Clock B. As the mechanism was tuned it became clear that Harrison's claims were no empty boast. The running was eerily smooth and it was felt that his claim should be tested. Could the 300-year-old ideas of a maverick carpenter allow a clock to lose just one second in one hundred days?

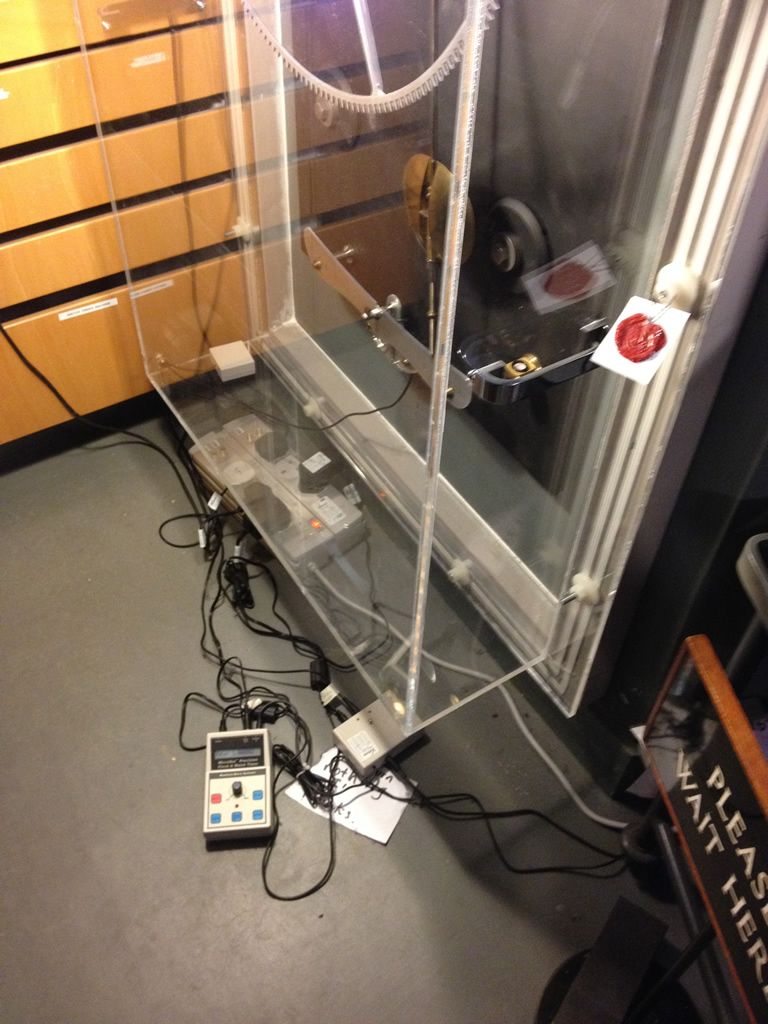

In March of this year the clock was moved to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich where it came into the care of Jonathan Betts. After preliminary tests in the horology workshop, the clock was locked into a glass cabinet on April 1st 2014 and sealed by representatives for the National Physical Laboratory and the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.

Older mechanical clocks are particularly susceptible to atmospheric change. Hot or cold weather will cause them to run fast or slow. Harrison invented a number of ingenious ways to compensate for this including his famous bimetallic strip, a bar composed of complimentary metals that shrink and expand to compensate for each other.

In the session just before lunch Jonathan Betts stepped through the wide range of atmospheric conditions experienced during 100 days of testing. Clock B reacted quicker than a traditional heavy bob pendulum but also stabilised faster. In a nail-biting last few minutes he revealed that Clock B had officially achieved what Harrison had claimed. There was a cheer from the attendees! On the 300th anniversary of the Longitude Prize, the unconventional ideas of its prizewinner had yet again been proved correct.

Time for lunch.

One by one we left the NMM building and trekked up the hill to visit the horological workshop inside the Royal Observatory. It's a tiny room stacked with history. The radio pips play through the speakers and on the far wall was Clock B, still sealed and in its case. On the wall next to it was Graham no. 3, the same regulator used by Nevil Maskelyne to test Harrison's seagoing clocks.

Returning back to the NMM, Burgess' colleague Mervyn Hobden spoke about the history of the Harrison Group - a group of Harrison devotees founded in the 1970s to discuss and further the horological ideas of John Harrison. Finally Will Andrewes gave a personal introduction to Martin Burgess, his life and his achievements and then Martin was able to speak.

There's a lot of Harrison in Burgess. He interrupted, he spoke his mind, and he chastised the attendees. I liked him. He was honest and sincere when he talked about the profundity of Harrison's ideas and how he had put those into practice in Clock A and Clock B. Sadly the clock beat us and there was no time for a panel but the day ended on a high and a standing ovation for Martin Burgess.

The ideas of a genius clockmaker had been proved correct 300 years later by an incredibly dedicated and talented group of individuals. This was long news.